Clarence Fountain grew up in a churchgoing and musical family in Selma, Alabama. His parents, William and Ida Fountain, were both active in the church choir, and often sang at home. Clarence lost his sight at age two, and at age eight, he enrolled in Alabama's Talladega Institute for the Deaf and Blind. There he joined a large boys choir and learned to read music in Braille. Inspired by the weekly CBS radio broadcasts of the Golden Gate Quartet, a popular gospel group of that time, he and his friends decided to start their own gospel singing group. They applied the musical skills they were taught in school and began writing and arranging songs. Calling themselves the Happyland Singers, they soon changed their name to the Blind Boys and started singing together as a sextet in 1939. They moved to Birmingham and performed daily on radio station WKAX.

Early on, the Blind Boys emulated the "jubilee harmony style," which had originated in the nineteenth century among minstrels and black college quartets and reached the height of its popularity in the 1930s through records and radio broadcasts. By the 1940s, however, the jubilee harmony style evolved into "gospel" group singing. This style featured a shouting and preaching lead singer, often accompanied by a rhythm and blues-influenced instrumentation, including electric guitar, piano, and sometimes horns and drums. Additionally, it made use of stronger rhythms and vocal techniques, such as moaning, melisma, and falsetto. By contrast, jubilee groups stood up straight and acted more restrained.

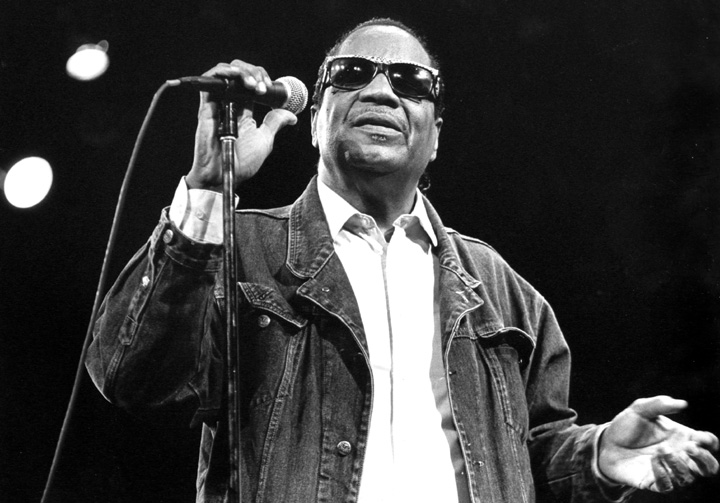

The Blind Boys were at the forefront of this transition. Skillfully mixing precise four-part harmonies with soaring lead vocal shouts and a driving rhythm and blues-based accompaniment, they quickly rose to prominence as premier interpreters of the postwar "hard" gospel sound. The group's style was nicknamed "house-wreckers," a term that refers to their ability to "shout" the church audience by stirring their listeners into states of spiritual ecstasy. Fountain said, "You have to feel the spirit deep in your gut, and you have to know how to make someone else feel it."

By the late 1940s the Blind Boys were touring full-time, performing for segregated audiences in churches and schools. In 1947, after the accidental death of lead singer Velma Trailer, the group reorganized and Fountain shared the lead singing with Reverend Paul Excano, who eventually left the group. Under Fountain's direction, the Blind Boys had their first hit recording in 1949 with "I Can See Everybody's Mother But Mine." According to Fountain, "Suddenly we were hot stuff, playing for audiences of 1,000 or more. We were on the upswing, and Ray Charles's manager offered us a big deal to go on tour performing rock, soul, pop -everything, really, but gospel. So, naturally, everybody in the Blind Boys, including our manager, wanted us to go pop, to become really big time. Except me, that is. See, I was head of the Blind Boys, I was the lead singer. And there was no way we were going to go pop or rock. Who needed it? Our bellies were full, we had no headaches, we were happy. At least, I was happy singing real gospel."

In 1953, the Blind Boys began a successful five-year association with Specialty Records in Los Angeles, but ultimately left the label because of renewed pressure to cross over to rock 'n' roll music. Fountain refused, and later commented, "The Blind Boys have devoted our lives to serving the Lord."

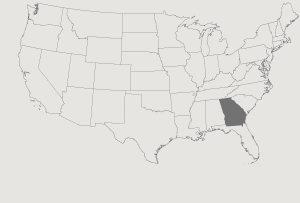

Despite opportunities to popularize their music, the Blind Boys continued to perform their hard-driving traditional gospel sound, touring around the United States and abroad. By the early 1980s, Fountain and the Blind Boys had been renamed the Blind Boys of Alabama and featured the legendary bass singer J. T. Clingscale, from the Blind Boys of Mississippi. In 1983, they received national acclaim for their performance in the dramatic production Gospel at Colonus, a contemporary adaptation of Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles. The drama is set in a black Pentecostal church. The Blind Boys sang the role of Oedipus, the blind king of Greek tragedy.

Fountain, George Scott, Johnny Fields, and Jimmy Carter have been with the group since its inception. The group has grown and changed along with the times, adding new members as needed. Gradually over its five-decade career, the ensemble modernized its sound by adding more vocalists, guitar players, and a drummer. Sometimes they sing in four-part harmony; sometimes they expand to six-part harmony. Fountain says the group owes its success to God: "We started to run [tour] in 1944, we started runnin' and singing for the Lord, and it wasn't nothing but the hand of the Lord that brought us through all these years and made us what we are."