Culture Native American

- African American

- Afro-Cuban

- Alaska Native

- Anglo

- Apache

- Armenian

- Asian

- Basque

- Brazilian

- Cajun

- Cambodian

- Chinese

- Chitimacha

- Cochito Pueblo

- Comanche

- Creole

- Croatian

- Crucian

- Czech

- Dakotah-Hidatsa

- Danish

- Ethiopian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- French

- German

- Ghanaian

- Greek

- Guinean

- Gypsy

- Haida

- Haitian

- Hispanic

- Hmong

- Hocak

- Hunkpapa Sioux

- Hupa-Yurok

- Inupiaq

- Iranian

- Iraqi

- Irish

- Isleño

- Italian

- Japanese

- Jewish

- Kashia Pomo

- Kiowa

- Klickitat

- Korean

- Lakota Sioux

- Laotian

- Lebanese

- Lummi

- Menominee / Potowatomi

- Mesquakie

- Mexican

- Mohawk

- Native American

- Native Hawaiian

- Navajo

- Nez Perce

- North Indian

- Norwegian

- Odawa

- Ojibwe

- Okinawan

- Omaha

- Oneida

- Osage

- Passamaquoddy

- Peruvian

- Polish

- Pontic

- Puerto Rican

- Pyramid Lake Paiute

- Sac and Fox/Pawnee

- Salish

- Santa Clara Pueblo

- Scottish

- Serbian

- Serbo-Croatian

- Shoshone

- Skagit

- Skokomish

- Slovak American

- Slovenian

- South Indian

- Swedish

- Tewa

- Tibetan

- Tidewater

- Tlingit

- Tolowa

- Trinidadian

- Ukrainian

- Vietnamese

- Wasco

- Western Mono

- Yakama-Coleville

- Yup'ik

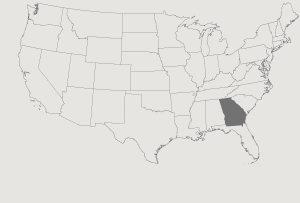

Artist Georgia Harris

- Horace P. Axtell

- Mary Holiday Black

- Lila Greengrass Blackdeer

- George Blake

- Alice New Holy Blue Legs

- Loren Bommelyn

- Bruce Caesar

- Walker Calhoun

- Helen Cordero

- Rose and Francis Cree

- Mary Louise Defender-Wilson

- Rose Frank

- Mary Mitchell Gabriel

- Sophia George

- Pat Courtney Gold

- Ulysses "Uly" Goode

- Georgia Harris

- Gerald R. Hawpetoss

- Evalena Henry

- Violet Hilbert

- Nettie Jackson

- Everett Kapayou

- Clara Neptune Keezer

- Maude Kegg

- Agnes "Oshanee" Kenmille

- Kevin Locke

- Esther Martinez

- Eva McAdams

- Nellie Star Boy Menard

- Gerald "Subiyay" Miller

- Vanessa Paukeigope Morgan

- Doc Tate Nevaquaya

- Grace Henderson Nez

- Oneida Hymn Singers of Wisconsin

- Julia Parker

- Georgeann Robinson

- Margaret Tafoya

- Ada Thomas

- Fred Tsoodle

- Chesley Goseyun Wilson

- Molly Neptune Parker

- Ralph Burns

- Pauline Hillaire

- Henry Arquette

- Yvonne Walker Keshick

- Rufus White