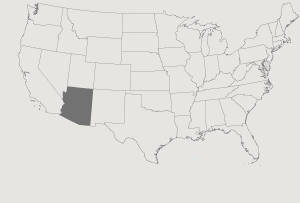

While growing up on the San Carlos Apache Reservation in southern Arizona, Evalena Henry attended the Rice School in San Carlos and the Globe School in Globe, Arizona. Her mother, Cecilia Henry, was a basketmaker and was considered by fellow tribal members of her tribe to be the matriarch of San Carlos basketry. "Ma [born in 1901] lost her mother when she was 3," Evalena said. "Her grandma took her and her sister Elsie in 'cause there was no one else to care for them. They all traveled around together on their horses through the mountains. Their grandma would go into town every month to trade baskets for everything else they needed. Nobody used money in them days. The old lady didn't want them to go to the white school. She wanted them to learn baskets and the old ways."

The Ineh (The People), or the Apache as they are known, are a large group of Athabaskan-speaking people who historically had occupied a large portion of the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Because Apache bands relied on hunting and covered great distances on horseback and on foot, they needed baskets that were relatively lightweight, durable and compact. Cecilia Henry continued to make baskets until she was 89 years old, when poor vision and Alzheimer's disease made it impossible for her to work.

Evalena learned to make baskets from her mother when she was 15. "My ma taught me the Apache way," she said. "She never asked me if I wanted to weave. I just started doing it, just by watching her. I started learning how to split the [willow] sticks — you know, you got to do it with your teeth. They got to be even. I kept trying for a week, and Ma finally said it was OK, but now I got to make it smooth. Then after more days she said it was OK, but now I got to make each strand thin, almost like paper. It took me three days to get it thin without breaking them!"

The designs on Henry's baskets vary: Some have very simple and straightforward bands or lines, while others have elaborate deer patterns — sitting or standing on stair-steps. Sometimes she uses elaborate borders and veers from traditional designs, incorporating Crown Dancers (sacred and magical dancers who take part in healing ceremonies).

The San Carlos Apache are well known for three distinct types of baskets: coiled trays and plates made mostly of cottonwood; the tus, an urn-shaped water container; and the burden basket. The tus and the burden basket are both twined woven and made primarily of cottonwood, squawberry, mulberry, cat claw, devil's claw and other willow species.

Around 1977, people began asking Henry to make burden baskets for the Sunrise Dance, a coming-of-age ceremony for 12-year-old girls. These baskets, Henry said, must be beautiful, with the young woman's name woven as part of the design, and strong because many sacred objects are placed inside. Since then, she has continued to make ceremonial baskets upon request from tribal members, though she also sells her work to art collectors. Though she had worked various jobs to support herself, she was able in her later years to devote more time to making baskets and teaching basketry to young people.

"My kids have picked it up. They've watched me. I think they're doing better than I did — real good at getting new designs. My youngest, she won a first prize, and she's in the fourth grade. She's getting better, and we all weave together."