Everett Kapayou, of the Mesquakie settlement in Tama, Iowa, was the last of five children. His mother, Lucille Kapayou, was a flute player of Mesquakie sacred and secular melodies. Everett learned much of his repertoire from her, first learning the melody from her flute playing, then having his mother — who did not sing — recite the texts for him to memorize, and finally putting the two together to sing the song. Kapayou's parents taught him their native language at home, and he learned English at school.

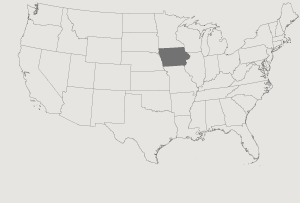

Stylistically, the Mesquakie, meaning literally "Red Earth People," have been influenced by a variety of neighboring tribal cultures and contemporary pan-Indian trends. During the seventeenth century, they were based in Wisconsin and came into contact with Algonquin-speaking tribes, such as the Potawatomi and Menominee. By the nineteenth century, they had resettled in Iowa and absorbed some of the cultural traits of the Eastern Plains and Prairie buffalo-hunting tribes such as the Omaha and eastern Sioux.

In the twentieth century, the homogenizing effects of non-Indian and pan-Indian popular culture threatened the integrity of indigenous traditions. Through his singing, Kapayou worked to maintain the Mesquakie way of life. "In the old times," Kapayou said, "songs were connected with anything an Indian did. Like the songs I sing are love songs; that's for courting. And [songs] for the ceremonies for health and everything for the people, and then, for harvest dances ... when you had an abundance of pumpkins and corn ... when your garden came up pretty good, then they had dances for that, and so forth. Everything that an Indian did had a song to it."

Kapayou's songs are a strong reflection of the distinct identity of the Mesquakie people. Though he was forced to labor long hours as a mason and construction worker, he actively participated in tribal ceremonies, but never sang religious songs outside of the context for which they were intended. "The ceremonial songs are sacred," he said. "We don't sing them to the public or nothing. They stay with where they're being sung at. At the moment, we have about six different clans. And I'm of the Fox clan and they have the Wolf clan and the Eagle clan and the Thunder clan and on down the line. And each of them, when they conduct a ceremony, they fast all day. The ones [the clan] that put on the ceremony, they're the ones that do the singing."

Despite his reluctance to sing sacred songs in public, Kapayou did feel his secular songs might serve as a catalyst for preservation and a vehicle for increasing awareness of Mesquakie traditions. "Most of the songs that I sing are called mood songs," he said. "Whatever you feel like, if you want to serenade somebody or if you want to console somebody or if you want to make them feel bad with a song, you can." In addition, Kapayou sang at social dances and powwows; he especially liked to sing 49 songs.

"A 49 song is a entertainment song," he said. "The people dance around a drum, and there's another dance they call a round dance that's similar to that, but a 49 is a faster beat than a round dance beat."

Kapayou was most renowned for the love songs he learned from his mother. These songs are especially significant because they recount intimate aspects of cultural heritage and demonstrate the enduring strength of the oral tradition.