Fatima Kuinova was a native of Samarkand, Tajikistan, in Soviet Central Asia, one of ten children. She grew up speaking Russian, but her cultural life was rooted in Bukharan Jewish traditions. Though her father, cantor of the local Bukharan Jewish synagogue, died when she was6 years old, she credits him with her earliest and deepest musical influence. She began singing as a child and started vocal studies when she was 14, performing as a teenager in school choirs and at festivals in Dushanbe, the capital. She sang on Soviet radio as early as 1941.

Because of the widespread discrimination against Jews under Stalin, she took the name Kuinova to hide her true identity. Her Jewish name was Cohen, and throughout her life she has retained the Kuinova. She even sang for Stalin himself, but he probably didn't know she was Jewish.

During World War II she sang for soldiers throughout Central Asia and in war zones. In 1948 she was named Honored Artist of the Soviet Union. In 1949 she began studying shashmaqam, the traditional music of her region. She worked with both Muslim and Jewish musicians. Kuinova explains that the texts, many of which date from the fifteenth century and deal with mystical love, are as important as the melodies.

Shashmaqam is related to, but recognizably different from, Persian, Ottoman and Arabic court music. Kuinova's repertoire reflects the multifaceted role that Bukharan Jewish singers fill in Central Asia, playing music for a wide range of functions. They were among the most distinguished musicians in the courts of the Muslim emirs and khans who ruled the region prior to its incorporation into the Soviet Union. The Bukhara emirate was taken over by the Soviet Union in 1920 and became part of the republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. In the Soviet period, traditional singers worked alongside Uzbek and Tajik musicians in radio station ensembles, music schools and concert halls. They also provided music for a variety of ceremonial and ritual occasions in the Jewish community and for the majority Moslem population. Since the 1920s, when the musical tradition was first documented by Soviet ethnomusicologists, it has been transcribed and taught from one generation to the next.

In some ways similar to the Indian raga, maqam (as it is known among Arabic, Turkish and Central Asian Jewish peoples) or dastgah (among Persians) is based on a system of modal scales with associated melodic themes, rhythmic modes and extensive improvisation. Although the similarities of principles and musical practice suggest the connectedness of a great tradition shared by Ottomans, Arabs, Persians and others, the particulars of regional and local practice vary significantly, and there are many distinctive localized styles.

For twenty-seven years, Kuinova belonged to an ensemble of women rebab (vertical violin) players. She toured widely with her ensemble to Kiev, Leningrad (St. Petersburg), and Moscow, within the former Soviet Union, and abroad to Europe, Afghanistan, and Iran, where she sang for the late shah.

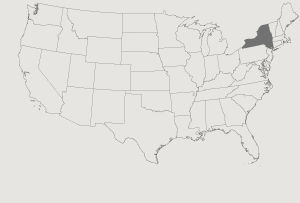

She immigrated to the United States from Tajikistan in 1980 to join relatives who were already settled in New York. There, she soon became a well-established member of the Bukharan Jewish musical community. Kuinova first worked in a trio or quartet in which her vocal line was accompanied by two or more doire — the Central Asian frame drum, or tar, a plucked-string instrument of the region — and this ensemble has become a focal point of the growing Bukharan Jewish community centered in Queens and Brooklyn.

In New York, Kuinova has performed for a variety of social occasions and concert events, and she has been in demand among Muslim emigrés as well as in her own community. In 1986, her shashmaqam ensemble was invited to perform in the Salute to Immigrant Cultures at the Statue of Liberty Centennial.