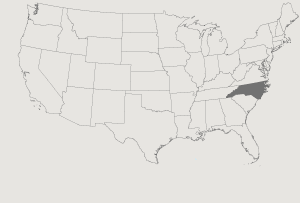

Etta Reid came from a family of mixed African American, American Indian and Irish ancestry in Caldwell County, North Carolina. As a child, she awoke to the smell of breakfast cooking and the sound of her father's guitar. She said that she began to pick the guitar when she was so small that she had to lay the instrument on the bed, stand on the floor and fret from the top. Her grandfather was a banjo player; her father played banjo and fiddle as well as guitar; her mother, harmonica and Jew's harp. Her sister Cora was also a superb instrumentalist, and many of her cousins played and sang.

Etta met Lee Baker, a piano player, at a square dance after a "corn shucking." They courted for six years and married in 1936; together, they had nine children. They lived in Lenoir, North Carolina, where Lee worked as a mechanic until the mid-1940s, when the family moved to Morganton to take advantage of a better school system. In Morganton, Lee took a job in a furniture factory. In 1949, Etta started working at the Skyland Textile Company, where she was employed for more than twenty years. Lee did not like traveling to perform music as much as Etta did, and he objected to her leaving home.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the demands of family and work forced Etta away from public performances. She said her husband didn't want her "to be gone away from home, but he loved my music." Etta was determined to continue playing the guitar and preserving the musical traditions she loved. She performed often at home in the evening, teaching her children and encouraging them to join in.

In 1956, while vacationing at the Moses Cone Mansion in Blowing Rock, in the mountains of North Carolina, Lee and Etta met Paul Clayton, a musician and recording agent from New York. At the urging of her husband, Etta played a few pieces on Clayton's guitar. Clayton was so impressed with Etta's playing that he came to the Baker home the following week to record her. Those recordings became part of an album, Instrumental Music of the Southern Appalachians, which appeared that same year. In addition to Etta's five solo guitar pieces, the album features her father, Boone Reid, her sister Cora and her brother-in-law Theopolis "The" Phillips. This album attracted considerable acclaim as one of the first commercially available recordings of African American banjo music. It made Etta legendary, especially among young urban musicians who began emulating her style.

In 1964 Lee suffered a stroke and Etta devoted herself to his care and therapy until his death three years later. She worked full time at the textile mill but yearned to pursue a musical career. In 1972, she was featured on another album, Music from the Hills of Caldwell County, along with her sister Cora, her cousin "Babe" Reid, and their husbands, "The" Phillips and Fred Reid. The following year Etta left her job at the textile mill to concentrate on her music. She said, "One day I just got to thinking about it. It was time to leave there and do something else."

Throughout her life, Etta worked to perfect her guitar style. She preferred not to sing, saying that her guitar could speak for her. She picked six- and twelve-string guitar in a two-finger style that is associated with blues of the southern Piedmont. She said, "I want my music to be clear and not hit a string that's not necessary because that blurs the tune. I don't care for picks. I have a bunch of them, but I hardly ever use them because you can't separate the sound."

In the 1990s, her daughter Dorothy began to accompany her from time to time singing hymns. Much of her repertoire consisted of traditional tunes learned from family and friends. The tune "John Henry" is one of the first pieces that Etta learned from her father, and it is the only tune she played with a slide.

Etta also composed music. She recalled hearing chords in her sleep while at the 1980 World's Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee, and she got up during the night to work out the chords on Cora's guitar. The following day she told the crowd that she had composed a tune but hadn't named it yet. She played her new tune, and the crowd named it "Knoxville Rag." Another of her compositions, "Broken-Hearted Blues," was unusual in that it featured her vocal. Over the years she adapted a variety of genres to her two-finger picking style, including old-time mountain dance tunes, boogie-woogie, gospel, rags and breakdowns and some modern pop music.

In addition to her love for music, Etta had a passion for gardening. She raised and canned her own produce. She constructed a hothouse in her backyard so that she wouldn't have to give up gardening in the cold weather. Each fall she went into the mountains to gather star root, ginseng, yellowroot and other herbs to make her own folk remedies.