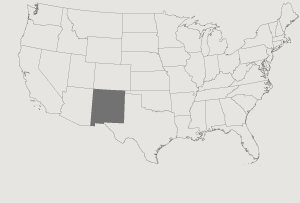

George López came from the village of Cordova, situated in a small valley of the Sangre de Christo mountain range north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Cordova, one of the early Spanish settlements dating from the sixteenth century, has become widely known throughout the United States and Europe for its tradition of religious wood carving.

López grew up in the fervent Catholicism of the region, and as a boy he watched his father, José Dolores López, carving santos, in the manner he had learned from earlier generations of the López family. Santos, literally "saints" in Spanish, include not only images of saints but apparitions of the Virgin Mary, depictions of the life of Christ and other religious scenes, Bible stories, and characters.

The craft of the santero arose from the Counter-Reformation in Spain and the work there of its greatest artists — El Greco, Velázquez and Murillo. These painters were at the peak of their careers when New Mexico was settled, and copies of their oil paintings were brought to the New World. Then, after indigenous Indians destroyed many of these models during the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680, a folk art emerged that depicted in wood carvings the effigies of Catholic saints. Often, the saints were represented in scenes that had a particular relevance to where they were made in New Mexico during the periods of Spanish colonial and Mexican rule. For example, San Ysidro Labrador with plow and oxen became the farmer's aid in arid land. St. Michael killing the devil, and St. Francis were also very popular.

Although López liked whittling as a boy, he did not pursue a career as a santero until later in life. He left Cordova at the age of 19 and worked with the Denver and Rio Grande Western's narrow-gauge lines in New Mexico and Colorado. Later, he got a job with the Union Pacific Railroad in Rawlins, Wyoming. Then, during the long, lonely nights in railroad camps between jobs, he started making small figurines similar to the ones he had seen his father and grandfather make. His first significant piece, he recalled, was the "Tree of Life," which he originated as a kind of Adam and Eve creation story "without the snake." He got the idea from a Garden of Eden carving his father once did, showing a serpent wrapped around a tree of forbidden fruit.

López worked in Los Alamos through World War II and until 1952, when he decided to devote himself full-time to wood carving. Working mostly with a penknife, a handsaw and sandpaper, he was able to produce a simple figure in about an hour. Other figures took several weeks or months to finish.

"It's part of my life, and part of my name ... I'm a sixth-generation santero," López said, "but I guess I'm the last because I've got no kids of my own." However, to perpetuate this venerable tradition, López passed on his skills to his nieces and nephews. Like his forebears, López did other woodwork in addition to his religious subjects, and carved animals, such as burros, sheep and goats, but he always preferred the traditional santos figures — St. Francis, St. Joseph, San Ysidro Labrador, St. Michael, the Virgin of Guadalupe and Santo Niño de Atoche. He viewed his work as a distinct mix of Catholic tradition, medieval Spanish art, mountain isolation and Penitente ritual. Of these, the influence of the Penitentes was perhaps the most pronounced.

The Penitentes (penitent brothers) are an offshoot of the Third Order of Saint Francis, a Catholic lay body known for benevolent acts. Members attend the sick, bury the dead and hold devotional services where there are no resident priests. "All my life," López said, "I've seen Penitente processions pass my house. In the old days, they'd have a procession when somebody died or even to say prayers at a sick person's home. Nowadays, they just have processions in Holy Week."