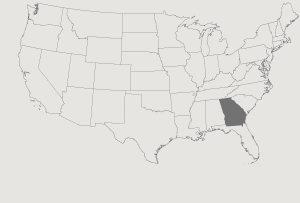

AhThe McIntosh County Shouters are the principal, and one of the last, active practitioners of one of the most venerable African American song and movement traditions — the "shout," also known as the "ring shout." The ring shout, associated with burial rituals in West Africa, persisted among African slaves and was perpetuated after emancipation in African American communities, where the fundamental counterclockwise movement used in religious ceremonies integrated Christian themes, expressed often in the form of spirituals. First written about by outside observers in 1845 and described during and after the Civil War, the shout was concentrated in coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia.

The patriarch of the McIntosh County shouters was Lawrence McKiver, who grew up with the other members of the group in the rural area around Briar Patch, Georgia. In explaining the origins of the shout, he said, "In slavery times, the old folks couldn't talk to each other. They had to make signs ... make the sounds we singing. That's why we sing in these old slavery sounds ... they couldn't talk, so they sang a song and they'd get together underneath the song that we're gonna sing."

McKiver was the group's lead singer or "songster," the one who starts, or "sets," a song before the shouters join in. The songster often improvises on the song's theme and then ends the song at the right moment. Accompanying him is the "stickman," who beats on the wooden floor with a thick hickory stick to control the rhythmic pace. "I can set 'em, and once they get it," said Benjamin Reed, who served as stickman at the time of the award. "I can turn 'em loose ... and I can bring 'em back right where I want 'em." Other members clap their hands in an interlocking rhythmic pattern. Joining in the singing are the lead "baser," who guides the shouters in the choral refrain; the shouters themselves; and possibly a third man who improvises solo on the text or joins in the refrain.

When the song hits its stride, the shouters, women dressed in head-rags of their grandmothers' day, begin to move counterclockwise in a ring. Religious rules prohibit the shouters from raising their feet high off the floor or crossing one foot over the other, so they move in the shuffling fashion characteristic of the "holy dance," often stooping over and moving their arms to pantomime the song in a fashion reminiscent of African custom. The songs are sung to many different melodies, their themes ranging from biblical vignettes to biblical themes transmuted to speak of worldly conditions, such as those under slavery, to contemporary topics, such as the scourge of drugs and the death of a fellow shouter.

Shouts were frequently planned to coincide with holidays and other special occasions. Elizabeth Temple learned the shout when she was a child and recalled that "long time back ... they used to have a shout at the church, Mt. Calvary Baptist Church, every Christmas, they would have a big shout. And we would follow them. I would follow my mother ever since I was 7, 8, up until now." McKiver also remembered the Christmas shout and added, "Christmas Eve ... we'd start shouting from 10 [at night] until daylight, and then we'd go from house to house and shout until New Year's coming and be singing these sounds and drinking coffee and eating biscuits or cornbread — that's all we got to eat — or sweet potato."

The McIntosh County Shouters first began performing outside their community around the Mt. Calvary Baptist Church in Briar Patch in 1980, when they appeared at the Georgia Sea Islands Festival on St. Simons Island. Since then, McKiver said, "I resigned from my church choir ... and I decided that I would teach the songs on the road, and that's what I've been doing." The McIntosh County Shouters have presented the shout at the National Black Arts Festival and elsewhere around the United States. Though members have become inactive or passed on, the Shouters continue to perform. Combining old and new traditions, the group has a website, http://mcintoshcountyshouters.com.