Mone Saenphimmachak was raised in Mahasai, a small village in central Laos. As a child, Mone observed her mother's skill at many forms of needlework. When she was 12, Mone began in earnest to learn the techniques of weaving and embroidery at which she was to become so skilled. "When I start weaving, it makes me sad," she said. "I remember when my mother teach me. I keep the weaving all the time because I am Lao people."

Many of the weavings Mone watched her mother make were decorated with traditional Lao embroidery, using one or two techniques: the tiny counted cross-stitch or the counted surface satin stitch. Both are accomplished on the closely woven grid of cotton aida cloth. The satin stitch is used primarily to embellish the solid-colored sarong worn by Lao women on special occasions. The cross-stitch, though sometimes used to make a border on a sarong, is traditionally applied in the decoration of bags, pillows, and other household items.

When Mone married her husband, Vanxay Saenphimmachak, he discovered that his own skills were lacking. "Usually a man learns how to make a loom from his father, but my father had a cargo boat, and he traveled a lot. I never learned from him," he said. "When I got married to Mone, her father laughed at me and said, 'Why did you get married if you don't even know how to make a loom?' I was embarrassed and studied with him very hard. After one year, I was able to make a pretty good loom for Mone. Then she could weave clothes for our family and sell some to make a little money."

The area in which the couple grew up was influenced strongly by Indian civilization. Part of this cultural legacy was a tradition of fine, highly decorative weaving and precisely executed embroidery marked by intricate geometrical designs and motifs of everyday life, such as elephants, deer and roosters.

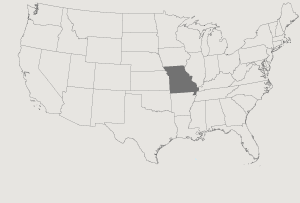

After the Communist takeover of Laos in 1975, the couple left the country. They and their four children were eventually resettled in St. Louis, Missouri. The culture shock was severe. But Mone soon found that her skills at weaving and embroidery could help to translate Lao culture to succeeding generations in her new homeland. She weaves, she says, "so Lao people love one another.... And we may recognize ourselves by those patterns."

Vanxay has made several looms, allowing his wife to teach others or to work on several pieces at once. His looms became more elaborately decorated works of art in their own right. "Only women weave, but they cannot weave unless men make looms for them. Men build the wood part and women tie the threads together to make a new warp. Then men and women work together to put the warp threads onto the frame he has built. Only men or only women is no good. You have to both finish the loom."