As a young man living outside Tucson, Arizona, Alfredo Campos was immersed in Western ranching life and skills. He was especially fascinated by the beautiful horse gear made from pieces of rawhide and had a special interest in braiding the reata, the traditional vaquero lariat. "I was born and raised on a ranch, and I always liked braided horse gear, like we used to rope cattle with,” he said. “I did that kind of work in Arizona and still on the ranch. My parents, Dolores and Alfredo Campos, always had a little ranch, but my father had to do construction work, and he farmed. There were twelve kids, and he had to earn a living at whatever he could find. But we always had cattle. Life was good on the ranch. There was always something to do. I enjoyed riding horses, training horses, and working with cattle. We did everything off of horseback. We had to rope the cattle and brand them and earmark them. We didn't even have a squeeze-chute."

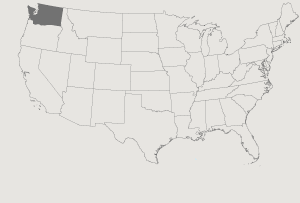

In 1958, he went on vacation to visit his brother in Washington state and decided to move there with his wife. He got a job working for Boeing. "But then I was drafted," he recalled, "and by the time I got out of the Army I had two girls. And when I came out, I had a good job. When I first started, I actually worked in the assembly of the body section of the aircraft, and from there, went into another shop that actually made sheet metal parts for the airplane power brake. And then, I became a lead worker for twenty-two years. I had from sixteen to eighteen people working for me. And then I became a fixture maker, which involved sharpening tools and making tools for punching holes in metal."

Campos continued to do some rawhide work. "I took it back up," he said, "but Washington state is on the West Coast and kind of a wet state. So, rawhide isn't very popular there. I learned about a little book by a man named Eugene Barnett that talked about horsehair hitching in the early part of the century. Well, I bought the book, and it was very difficult for me to follow. So, I put the book away and I started trying to learn it on my own and did a pretty good job. Now, the book makes perfect sense. I can follow him very well, and my hitching is more like when hitching was done more. It kind of died out."

In earlier days this art form was associated with prison life, to the extent that "making hair bridles" was synonymous with doing time behind bars. Campos points out that he has never been to prison, but he did study historic prison pieces in order to master the complex knots and designs.

Through the years, Campos taught himself every step in the process of horsehair hitching, from gathering hair to dyeing it and then figuring out the designs he wants to make in the actual piece. "I have to know how I want it to look. Some designs I make out on a graph paper, though I don't always follow them in their entirety. I start them out. Hitching is kind of a mathematical process in that you have to work with strands that are divisible by the size of the design you select."

Campos became widely known for his craftsmanship through a 1984 article in Western Horseman magazine. The impeccable precision, elaborate geometric patterning and vivid coloration of his quirts, headstalls, bosals and reins helped spur a revival of interest in horsehair hitching.