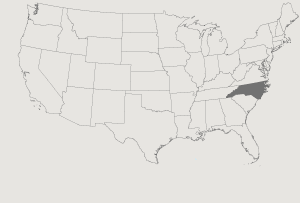

Bertha Cook grew up in Sands, a small community northeast of Boone in Watauga County, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. As a child, she accompanied her mother to Southern Highland Craft Guild fairs, where she learned about Colonial knotting and fringing in making bedspreads and pillows. She later learned the intricacies of this craft of knotting and tying from her mother and grandmother, who both worked alongside as she began doing her own work.

This style of needlework originated in the Colonial period and is related to candlewicking, although the technique is more difficult and the results more durable. Done with white thread on white cloth, the work has an elegance that results from the exactness of stitchery and the complexity of design.

Although she started learning to make knotted bedspreads at an early age, Cook was reluctant to learn fringe tying, the process of making and attaching rows of loops around the edges of a spread. In 1913, when she was 18 years of age, she learned to do the tying. She recalled, "My grandmother, my aunts, and my mother, they all did it. I never did want to tie it, but I did. I was married and had two children.... One day, Mama said, 'If you don't learn to tie fringe I'm gonna whip you.' So I didn't want to be whipped and I learned. Now I've been tyin' ever since."

Another motivation for her to learn was that bedspreads and other finished pieces could be sold, providing a little extra income for her growing family. She and her husband, Daniel Cook, whom she had married when she was only 16, had six children. "When you're raising a family of six ... it was a necessity to work, and if you learned a craft or anything you could get a nickel for, you done it," she explained. As soon as her children were old enough to help, Cook began teaching them to "knot and tie" so they could help her. The money she earned from selling knotted bedspreads and similar pieces helped pay for family cars, a new refrigerator and a replacement well.

Over the years, Cook made over a thousand bedspreads, as well as other items such as pillows, curtains, table runners, table covers, tablecloths, pillow shams and even a men's jacket. Patterns were handed from one generation to the next in her family: Bird in the Tree, Rose of Sharon, Bowknot and Thistle, Napoleon Wreath and Sunflower. Cook's personal contribution to the design repertoire was the lovely Grape Wreath, a stately figure with a circle of grapes and grapevine. Her sense of design and balance was nearly flawless, and she enjoyed improvising leaf shapes as she sewed. "You don't find any two leaves the same in nature," she liked to say, always inspired to go in new directions in her work, but never straying far from the traditions she embraced. "I like it because of the beauty of it."

Cook made her knotted bedspreads with large sheets of unbleached or whitened muslin decorated with patterns formed by small knots and, sometimes, other embroidery stitches with white thread. Twine fringe tied into intricate patterns trimmed the spread. To start a new spread, Cook placed a muslin sheet over an older spread. Using a rag and a bluing solution, she marked the raised areas on the new sheeting produced by the lines of knots on the old spread underneath. Gradually, a pattern of bluing dots begins to resemble the bottom spread's pattern on the muslin sheet. These dots become the pattern for the new spread. Cook then began knotting over the dots, using multiple plies of cotton thread that she twisted together in bundles. For her Grape Wreath spread, for example, she passed twelve plies through a large needle and primed the strands with beeswax to hold them together. She then pushed the needle and thread into the muslin, twisted the needle once and pulled it back out to form what her mother called "Colonial" knots. This method produced tight, neat knots that stand up on the bedspread. After the knotted pattern is completed the bluing is washed out

The final stage involves trimming the bedspread with rows of loops that form a fringe. Cook used a shuttle to form tied loops, making one hundred to a yard. She utilized dowels of different sizes to make a different size loop for each row. She then tied each row to the previous one, forming tiers of lace to be sewn onto the bedspread's edge. The rows of fringe were tied on a wooden frame her husband built for her. She affixed the loops to the spread using a briar stitch her mother taught her. This stitch gave the appearance that the fringe was tied through the hem rather than stitched on.

Cook joined the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild in 1951, and a year later she received the Guild's Excellence of Design Award. She was recognized again in 1973 by the Guild for her lifetime membership. For decades, Cook demonstrated at festivals and fairs throughout the country, including the North Carolina State Fair and the 1982 World's Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee.

In 1982 Cook fell and broke her hip and had corrective surgery. Her recovery was slowed by arthritis. Upon regaining her strength, she resumed knotting and making bedspreads for customers. With age, the pace of her work slowed. "I used to make one [bedspread] a week," she recalled. "Anybody who's ever made one will declare I was lyin', but I'm not. But the last time I made one, it took me one year and four weeks."