Burlon Craig was one of ten children raised on a family farm a few miles from the small town of Henry, in the Catawba Valley of Lincoln County, North Carolina. In addition to working the farm, his father was a preacher for the Church of God.

At an early age, Craig was exposed to the numerous alkaline-glaze stoneware potteries in this region along the western Piedmont of North Carolina that were established in the nineteenth century by early settlers.

When Craig was in first grade, he watched potter Will Bass mold clay. Growing up, Craig chopped trees on his father's land for local potter James Lynn, who used the wood to fire his kiln. Eventually, Craig learned pottery making from Lynn, watching him burn, make glazes and prepare clay. He worked with Lynn for about four years and turned his first successful pot by the time he was 14 years old. Later, he worked a mule for another local potter. "He didn't have a mule," Craig said. "I'd bring Daddy's mule and grind his clay for him. He would give me 25 cents for bringing the mule and grinding the clay. That was a lot of money back then."

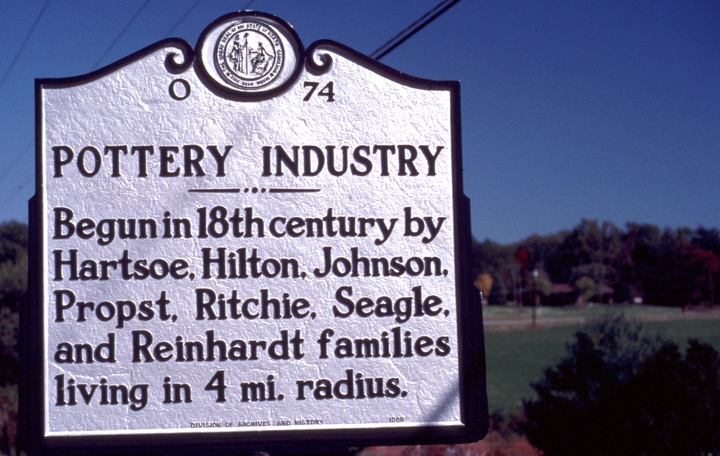

During the 1930s, Craig worked with a number of local potters, including Luther Seth Ritchie, whom he called Uncle Seth, and Floyd Hilton. During the summer of 1936, he worked for Enoch and Harvey Reinhardt, also well-known local potters.

During World War II, Craig served with the Navy in the Pacific. Upon returning to North Carolina, he bought Harvey Reinhardt's kiln and farmland. Craig settled there with his wife, Irene Lindsay, and to supplement his income as a potter and farmer, he worked in the North Hickory furniture factory machine rooms.

Until the late 1970s, Craig primarily made utilitarian stoneware for his neighbors -- churns, pitchers, jars, crocks, candlesticks and a few birdhouses and flowerpots. Encouraged by friends to make face, snake and ring jugs, he began to expand his repertoire to include face jugs ranging in size from miniature to 9 gallons, double face jugs, pitchers, monkey jugs, footed and unfooted ring jugs and more.

Over the years, Craig's techniques changed little from those used by Daniel Seagle and David Hartzog, who introduced alkaline glazing in this region in the mid-nineteenth century. Craig shoveled his clay from the bottomland along the South Fork of the Catawba River, then trucked it home to grind it in a pug mill. Next, he turned his jugs, jars, pitchers and other forms on his foot-powered treadle wheel, pulling up the walls of the pots as he pumped the flywheel with his left foot. His alkaline glazes were made from local -- usually crushed glass bottles, wood ashes, iron cinders, water and clay -- and then finely ground in a hand-turned, water-powered stone mill. Finally, he "burned" his wares in a huge wood-fired groundhog kiln, a long and arduous task lasting eight to ten hours. As the temperature rose far above 2000 degrees, the pots heated up to a white-orange hue.

One of the distinctive features of Catawba Valley pottery is a blue tint that appears in the glaze when the kiln temperature is white-hot. The blue is thought to be caused by the mineral rutile (titanium dioxide) that occurs naturally in the bottomland clay near a branch of the Catawba River. The blue is prevalent in many of Craig's pieces.

In the 1980s, Craig's shop became a mecca for students of the alkaline-glazed stoneware tradition, because, unlike other local potters, he retained all the old techniques. There is a purity to Craig's work: His shapes are elegant, the textures of his glazes rich and earthy. His long experience shows in the deceptively simple forms he favored. A generous man, he shared his skills and was patient with those who wished to learn from him.