Tradition Artisan

- Accordionist

- Advocate

- Appalachian

- Artisan

- Ballads

- Bandleader

- Banjo Player

- Basketmaker

- Beadworker

- Bess Lomax Hawes Award

- Blacksmith

- Bluegrass

- Blues

- Boatbuilder

- Cajun

- Capoeira Angola

- Ceramicist

- Clarinetist

- Composer

- Conjunto

- Creole

- Cuatro Player

- Dancer

- Dobro Player

- Drum Maker

- Drummer

- Egg Decorator

- Embroiderer

- Fiddler

- Flute Player

- Gospel

- Guitarist

- Hardanger

- Harmonica

- Hula

- Instrument Maker

- Kathak

- Klezmer

- Lace Maker

- Lindy Hop

- Luthier

- Mandolin Player

- Mardi Gras Chief

- Mask Maker

- Metalsmith

- Multi-Instrumentalist

- Musician

- Needleworker

- Ornamental Ironworker

- Oud Player

- Pianist

- Poet

- Polka

- Potter

- Prim Player

- Quillwork

- Quilter

- Regalia Maker

- Rosemaler

- Saddle Maker

- Santero

- Scholar

- Sephardic

- Shaker

- Shape Note

- Singer

- Skin Sewer

- Slack Key

- Snowshoe Designer and Builder

- Songster

- Songwriter

- Spiritual/Shout Performers

- Spoken Word

- Steel Drum

- Step Dancer

- Stick Dancer

- Stone Carver

- Storyteller

- Straw Appliqué Artist

- Straw Artist

- String Band

- Swamp Blues

- Tamburitza

- Tap

- Tea Ceremony Master

- Tejano

- Toissan muk'yu Folk Songs

- Tradition Bearer

- Trombonist

- Uillean Piper

- Ukulele Player

- Violinist

- Weaver

- Western

- Western Swing

- Wood Carver

- Work Songs

- Yiddish

- Yoruba Orisha

- Zydeco

Artist Sister Rosalia Haberl

- Yacub Addy

- Juan Alindato

- Eppie Archuleta

- Eldrid Skjold Arntzen

- Celestino Avilés

- Horace P. Axtell

- Earl Barthé

- Kepka Belton

- Earnest Bennett

- Mozell Benson

- Nicholas Benson

- Mary Holiday Black

- Lila Greengrass Blackdeer

- George Blake

- Alice New Holy Blue Legs

- Loren Bommelyn

- Laverne Brackens

- Jerry Brown

- Em Bun

- Bruce Caesar

- Dale Calhoun

- Alfredo Campos

- Genoveva Castellanoz

- Bounxou Chanthrapone

- Nicholas and Elena Charles

- Betty Piso Christenson

- Delores E. Churchill

- Gladys LeBlanc Clark

- Bertha Cook

- Helen Cordero

- Burlon Craig

- Rose and Francis Cree

- Belle Deacon

- Amber Densmore

- Bo Dollis

- Sonia Domsch

- Rosa Elena Egipciaco

- Nora Ezell

- Rose Frank

- Mary Mitchell Gabriel

- Sophia George

- Pat Courtney Gold

- José González

- Ulysses "Uly" Goode

- LeRoy Graber

- Gladys Kukana Grace

- Frances Varos Graves

- Sister Rosalia Haberl

- Charles E. Hankins

- Georgia Harris

- Dale Harwood

- Gerald R. Hawpetoss

- Evalena Henry

- Bea Ellis Hensley

- Mary Jackson

- Nathan Jackson

- Nettie Jackson

- Meali'I Kalama

- Clara Neptune Keezer

- Maude Kegg

- Agnes "Oshanee" Kenmille

- Norman Kennedy

- Bettye Kimbrell

- Don King

- Ethel Kvalheim

- Esther Littlefield

- George López

- Ramón José López

- Jeronimo E. Lozano

- Mary Jane Manigault

- Miguel "Mike" Manteo

- Sosei Shizuye Matsumoto

- Eva McAdams

- Marie McDonald

- Lanier Meaders

- Leif Melgaard

- Nellie Star Boy Menard

- Elmer Miller

- Gerald "Subiyay" Miller

- Allison "Tootie" Montana

- Vanessa Paukeigope Morgan

- Genevieve Mougin

- Mabel E. Murphy

- John Naka

- Grace Henderson Nez

- Yang Fang Nhu

- Luis Ortega

- Nadjeschda Overgaard

- Vernon Owens

- Julia Parker

- Elijah Pierce

- Konstantinos Pilarinos

- Hystercine Rankin

- Georgeann Robinson

- Eliseo and Paula Rodriguez

- Teri Rofkar

- Emilio and Senaida Romero

- Herminia Albarrán Romero

- Emilio Rosado

- Mone and Vanxay Saenphimmachak

- Losang Samten

- Duff Severe

- Harry V. Shourds

- Philip Simmons

- Eudokia Sorochaniuk

- Dolly Spencer

- Ralph W. Stanley

- Alex Stewart

- Nancy Sweezy

- Margaret Tafoya

- Jennie Thlunaut

- Ada Thomas

- Dorothy Thompson

- Paul Tiulana

- Lucinda Toomer

- Ezequiel Torres

- Nicholas Toth

- Irvin L. Trujillo

- Dorothy Trumpold

- Lily Vorperian

- Lem Ward

- Newton Washburn

- Gussie Wells

- Francis Whitaker

- Arbie Williams

- Yuqin Wang and Zhengli Xu

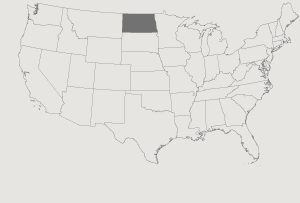

- Paul and Darlene Bergren

- Harold A. Burnham

- Molly Neptune Parker