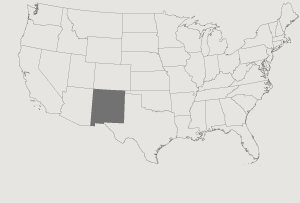

While growing up in Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, Margaret Tafoya learned the art of making pottery from her mother, who was an heir to the pottery tradition that had been passed on from one generation to the next for centuries by the speakers of the Tewa language in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico. Of the six pueblos where the Tewa language is spoken, the Santa Clara has long been noted for its pottery tradition, which emerged around A.D. 500, when the pueblo people developed agriculture and adopted a more settled lifestyle than that of their hunting and gathering ancestors.

For more than 1,000 years, pottery had been an important trade commodity among the Rio Grande pueblos, and archeological evidence demonstrates its widespread use among people of the region. With the coming of the Spaniards and other Europeans in the sixteenth century, pottery commerce continued; after the opening of the Santa Fe Trail in 1821, however, utilitarian pueblo-made pottery was gradually replaced by machine-made products. By the turn of the twentieth century, pueblo pottery was beginning to be identified as an art form in its own right and to be collected by anthropologists, historians, artists and patrons of the arts.

Tafoya's family, she said, had been potters "as far back as records exist." A 1983 exhibition at the Denver Museum of Natural History included more than one hundred pots by six generations of Tafoya family potters, the earliest made by her great-grandmother around 1934. But it was her mother, Serafina Gutierrez Tafoya, who was her greatest influence. Both Serafina and Margaret were best known for their ability to make unusually large pots — thirty inches or more high. These pots necessitated the digging of a special clay, months of careful drying of the unbaked body, a meticulous firing to achieve a uniform color and to prevent cracks, and many hours of polishing to achieve the desired mirror-like finish.

She made only hand-coiled vessels and used only clay dug from deposits on Santa Clara land. "We get the clay where our ancestors used to take it," she said. "My girls are still doing work from the clay that my great-great-grandparents used." Furthermore, she insisted that her descendants do likewise and required them to fire their wares with natural fuels in an open fire and to finish their vessels to the characteristic luster by rubbing their surfaces with a smooth stone.

Overall, Tafoya's work reflected the transformation of the Santa Clara pottery tradition from the utilitarian to the artistic. She adapted the general vessel shape; animal forms were appended in jars and bowls, but she helped revive the use of polychromes, the making of which had been discontinued by the late 1800s. She created polished red and black ware, decorated with impressed and carved (intaglio) designs, highlighted in matte buff, red or black against the polished surface. Unlike some of her contemporaries, who painted designs in matte black, buff and orange on black vessels and red, tan, ochre and blue-gray on red vessels, Tafoya always preferred the intaglio method. She often carved a "bear paw" design, introduced by her mother, on the neck of each large storage vessel. "It is a good-luck symbol," she said. "The bear always knows where the water is."

Tafoya also decorated her pots with water serpents, rain clouds and buffalo horns, all symbols of survival for her people. She was a traditionalist but also an innovator in the making of wedding, storage and water jars, plates, vases, lamps, candlesticks and other distinctive forms. As a teacher, she imbued her students with the values she had learned as a child. Her daughter, Toni Roller, and her grandchildren, Cliff Roller, Nancy Youngblood Cutler and Nathan Youngblood, have all been recognized for their pottery, and they, too, utilize traditional methods and at once preserve and broaden the scope of the tradition.