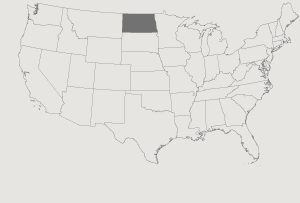

State North Dakota

- Alabama

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Puerto Rico

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virgin Islands

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington, D.C.

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Artist Rose and Francis Cree

- Rose and Francis Cree

- Mary Louise Defender-Wilson

- Sister Rosalia Haberl

- Paul and Darlene Bergren